Much Ado About Nothing Workshop

20-25 JULY 2020

In response to the current travel restrictions, BePeriod will gather for a week-long online workshop in Messina of the 16th century as painted by William Shakespeare. We will meet online every day of the week for two-hour sessions with intermissions. Each session will conclude with a practical exercise to be applied throughout the following day. Students’ verifications from this exercise will lay the ground for the following session.

Shakespeare’s works have deep roots. He drew from Ancient Greek and Roman plays, and Judeo-Christian myths, and wove them into theatrical dramas. We will use the key themes of his play Much Ado About Nothing as instruction and inspiration for self-study. Read more below…

1st Session – 20 July | 6pm / 8pm UTC – To be decided by availability of participants

Shakespeare Plays and Much Ado About Nothing

A general overview of Shakespeare plays. Comedies, tragedies, and histories. Shakespeare’s England. Levels of society and their corresponding manner of speech. Writing style and metrical patterns. Examples in Much Ado About Nothing. Division into Acts and Scenes. Key themes in Shakespeare’s plays.

Two key themes we will follow in Much Ado About Nothing:

- The blindness of love and subjectivity of eyesight

- Losing Paradise to value Paradise

We will superimpose the first theme over the Fourth Way idea of laws: law of accident, law of cause and effect, and law of fate. We will conclude by setting an aim to observe these laws in our inner world.

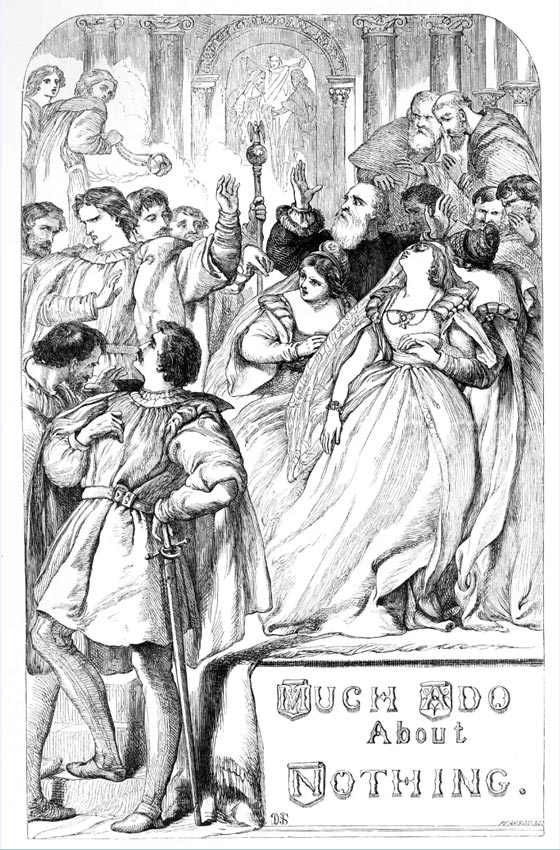

Much Ado About Nothing Full Page Introduction

What may happen to us depends upon three causes: upon accident, upon fate, or upon our own will… accidents cannot be foreseen. Today a man is one, tomorrow he is different: today one thing happens to him, tomorrow another.

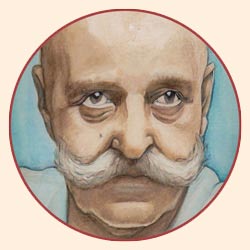

Cupid

2nd Session – 21 July | 6pm / 8pm UTC, TBD

The Blindness of Love and Subjectivity of Eyesight

“Did you take note of Hero, Leonato’s daughter?” Claudio asks Benedick in the first scene of Much Ado About Nothing. “She is the sweetest lady I ever looked upon.” Benedick disagrees, and a dialogue develops over how the same lady can look different in the eyes of two different people. This subjectivity of eyesight will continue throughout the play, driving the plot from comedy through tragedy and back to comedy.

In right order, attraction is governed by the law of fate. But this is not guaranteed and we will discuss the various elements that may enter attraction during this session. When Don Pedro takes it upon himself to bring Claudio and Hero together, he uses cause and effect to advance a fatal element. Ultimately, he proves successful, although not without trouble, because he doesn’t bring into consideration the law of accident.

The law of accident governs our daydreaming and associative thinking. We will conclude this session by setting an aim to observe the manifestations of the law of accident in our day to day lives.

3rd Session – 22 July | 6pm / 8pm UTC, TBD

The Hubris of Challenging Cupid

The masked ball of Act II is an obvious example of the blindness of eyesight, in this case deliberate. The occasion enables the evil Don John to deceive Claudio into believing that he has been betrayed by Don Pedro. “Let every eye negotiate for itself,” says Claudio, as he realizes how easily he has been misled. Nevertheless, this misunderstanding is quickly put aright and Claudio and Hero become engaged. Don John plots a new deceit, again by making things seem different than they are. He plans to make Hero seem disloyal in the eyes of her new fiancee, Claudio.

Hubris was a common tragic flaw in Greek theater. It meant excessive vanity, typically when man forgot his position and presumed himself equal to the gods. When Don Pedro decides to make Beatrice and Benedick fall in love with each other, he is challenging the God Cupid, as he himself confesses: “If we can do this, then Cupid is no longer an archer…” Don Pedro proves successful, although remains unsuspecting of a different plot set up by his bastard brother Don John, one that will now lead the course of events in a tragic direction.

“We do not see the world as it is,” says the Talmud; “We see it as we are.” Judgment perpetually clouds our vision. We will conclude this session by setting an aim to observe judgment and understand its relation to the law of accident.

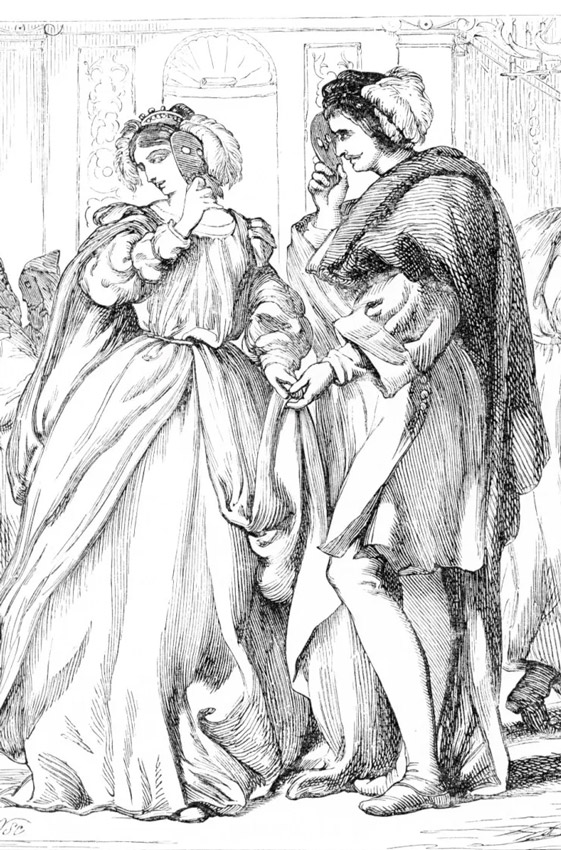

Don Pedro and Hero

The Watch

4th Session – 23 July | 6pm / 8pm UTC, TBD

Losing Paradise to Value Paradise

With the aid of his friends, Don Pedro puts his love-plot into practice. Benedick, hiding in the garden, overhears Don Pedro and his friends discussing how deeply Beatrice is in love with him. Then Beatrice, while likewise hiding in the garden, overhears Hero and her friends discussing how deeply Benedick is in love with her. The hiding in the garden alludes to Adam and Eve, who after biting from the Tree of Knowledge of Good and Evil, hid from God. This introduces our second key theme: the need of losing Paradise to value Paradise.

As this happens, Don John with the aid of his men also puts his evil plot into practice. Under the pretense of helping avert a big mistake, he tells Claudio that he shouldn’t marry Hero because she is disloyal. He can prove her disloyalty by showing Claudio and Don Pedro how Hero receives a visitor to her bed chamber at night. Here we return to our first theme; although Hero is truly loyal, Don John makes Claudio and Don Pedro see something that doesn’t exist. Don John’s plan succeeds, although his men are caught by Messina’s watch. When arrested, they confess their crime, but the news comes too late to alert the parties involved. At the wedding on the following morning, Claudio and Don Pedro still believe Hero is guilty, and come to shame her.

Is there an intelligence behind our deviations? We will conclude this session by setting an aim to observe whether there is an element in us that uses the law of accident to keep us asleep.

5th Session – 24 July | 6pm / 8pm UTC, TBD

Are Our Eyes Our Own?

The wedding in Much Ado marks the extreme of the blindness of love and subjectivity of eyesight. Claudio and Don Pedro have been deceived into believing Hero is disloyal. Beatrice and Benedick have been deceived into loving each other. In this tragic and comic scene, the entire wedding party is deceived. At its height, after throwing Hero back to her father, Claudio underscores this irony by asking the rhetorical question, “Are our eyes our own?”

The only two people attending, who are not deceived, are the evil Don John and the innocent Hero. We will discuss their internal significance.

After shaming Hero, Claudio and Don Pedro leave. Hero faints. Leonato her father denounces her. But the Friar who ministered the wedding suspects error and hatches a new plot: Hero will be taken into hiding, and news will be published that she has died. Her disloyalty will consequently seem irrelevant and her loss will rekindle Claudio’s love. “For it so falls out that what we have we prize not while we enjoy it,” explains the Friar, “but being lacked and lost, then we rack its value…” Paradise must be lost in order to be valued and regained. In this way, the climax of Much Ado knits together both key themes of our study.

We cannot increase our valuation for consciousness without suffering the loss of consciousness. We will end this session by aiming to observe and reconcile this seeming contradiction.

The Wedding

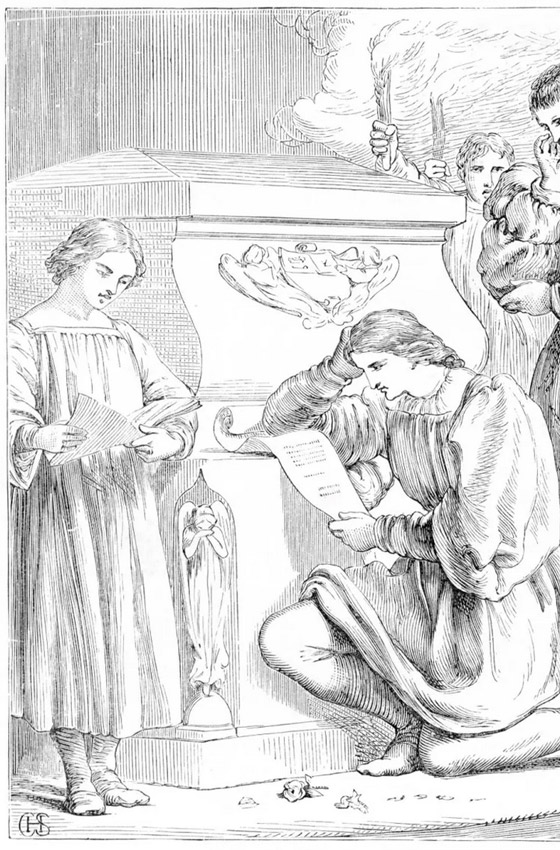

Claudio Mourns

6th Session – 25 July | 6pm / 8pm UTC, TBD

Another Hero | Higher Emotional Center

Don John’s scheme is brought to light and Claudio realizes his grave mistake. He asks Leonato, Hero’s father, how he can repent for his deeds, and receives the surprising answer: “Since you could not be my son-in-law, be my nephew.” Leonato will forgive Claudio on condition that he marry his brother’s daughter. He must do this blindly, without seeing her till after confirming his vow at the wedding. Leonato’s plan, of course, is to present the true Hero to Claudio on that occasion, veiled.

The solution to the blindness of love and subjectivity of eyesight is not to see. Here Shakespeare echoes several ancient traditions that portrayed the higher world as invisible to the lower. Invisible did not mean inaccessible; the higher had to be reached by means other than the senses. Accordingly, the last act of Much Ado features many references to the futility of sight, hinting that Claudio’s blindness and repentance afforded him the beloved he could never otherwise have obtained.

The higher is incomprehensible to the lower. And yet, we use lower centers to reach higher centers. How do we reconcile this contradiction? We will conclude this last session by outlining the gap between lower and higher centers, aiming to incorporate this understanding into our daily efforts to Be.

I wish to give up everything that I can think, and choose as my love the one thing I cannot think. For God can well be loved, but He cannot be thought.