Our Journey and Our Time

Older people who meet this work often wonder whether it is worthwhile starting. The journey seems so long and there is so much to learn. They fear their habits are ingrained and doubt whether they have enough time and stamina to alter them. When a person in the latter stages of their life asks for my opinion, I always recall the story of Donald Price.

Don was a member of the group I had joined when I first became involved in this work. It was small but healthily diverse, with members of all ages. Don was the oldest, longest-active member, as well as a foreigner, so we took him to be our superior. His loud voice and coarse laughter compounded this impression. So habitual was Don’s high volume and abrasive manner that, whenever we gathered together—at a restaurant, a garden party, or a field trip—we knew immediately if Don was there or not. His voice was the first to greet us. Because he was a foreigner, and older in age and in the work than the rest of us, no one challenged Don. We assumed that either there was some reason behind his manifestations that escaped us, or that his habits were so deeply rooted they were effectively irreparable.

One day, a senior practitioner from another country visited us. He was soon exposed to the loud talking and laughter of Don Price and was surprised to learn we had been accepting Don’s behavior so quietly and for so long. “But have you never pointed it out to him?” he asked. We looked at each other with embarrassment and guilt. We saw that we had shirked our responsibilities as students. Our visitor wasted no time in formulating the following task: Don was to restrict his conversation in our gatherings to no more than three sentences. If he could not, then he would have to stop attending them altogether.

It was customary for visiting practitioners to give tasks like this. Part of the aim behind their visits was to observe and advise group members how to break their own habits, or unhelpful patterns that had developed in the group—just as had happened with Don and the rest of us. Because of my command of English (I was the main translator for our visitor), I was chosen to monitor Don’s progress in the task he’d been given. I was in my early twenties; Don was in his late sixties. I was new to the group; Don was the oldest. I was shy and spoke very little; Don was vociferous and indiscreet. The lamb was chosen to monitor the lion.

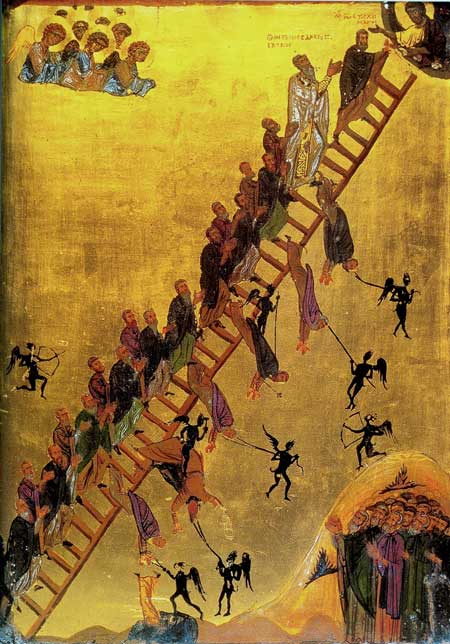

The Ladder of Divine Ascent | 12th c. C.E. | Monks climb up or fall off the path

We learn our limits by pushing through them. I still vividly remember picking up the phone, apprehensively dialing Don’s number, and hearing his rough “Hello?” on the other end. I recall having to remind Don who I was (he had hardly noticed me till that moment) and then delivering the visitor’s decision that I would be responsible for monitoring his progress. In the pause that ensued, I wondered whether I was now going to take the punch on behalf of everyone, but Don surprised me. “You’re right,” he said, in an entirely different tone of voice than I had ever heard him use. “It’s high time I learned to control my talking. Tell the group I’ll take these words to heart and respect the task I’ve been given—and that I’ll need their help.”

And so, while Don was invited to learn to speak consciously, I was invited to learn not to judge the potential of other students. Never think that others are incapable of receiving criticism. Never shrink from offering something that might be helpful for their inner work. Never imagine you know what others are capable or incapable of accomplishing.

The majority of our group remained unconvinced. It was difficult to believe Don would be able to rein himself in, no matter how genuinely he intended to do so. But Don proved us wrong. After needing to be reminded a few times, he learned to keep to his task, to lower the tone of his voice and restrict himself to no more than three sentences at any gathering.

A year went by. Don and I became good friends. I was obliged to speak with him on a regular basis and discovered that he was a gentle giant. No longer would we enter our gatherings and be greeted by Don’s loud voice and laughter. The lion had been tamed.

On the anniversary of this taming, some group members wondered whether it was time for Don’s task to come to an end, now that he had mastered it. Custom dictated that only the person who gave a task could rescind it. I was told to call the senior practitioner to ask his opinion. “We want to have as few rules as possible,” he said in agreement with our reasoning, “so if Don no longer needs the help of scaffolding to restrict his talking, we may as well remove it.”

But when I called Don to convey the good news, I could not get through. I tried several times without success. No one else in our group could get hold of him. Two days later, his son called me back, having seen my missed calls on Don’s phone. It turned out that, during the night before I had tried calling him, Don had died of a stroke.

●

The other lesson I learned from Don Price was how wrongly we perceive this work. Standing at its starting point and attempting to anticipate its trajectory, we assume it to be a journey from point A to point B, like mastering a language or learning to play the piano. We assume that if we have enough time and stamina, we will reach this goal—but this is nonsense. The differences between students are so great and so deep that our starting age and projected lifespan are irrelevant. There is no general point A and B, nor any general time limit. There is only our journey and our time. In this work, we run a marathon for ourselves against ourselves. As we persist, the work penetrates us more and more deeply until it merges with our fate. When it does, it holds a mysterious lesson custom tailored exclusively for us.

Master that lesson and you are free to go, just like Don Price.